Regenerative Metrics: An Oxymoron or a Missed Opportunity?

Hypothesis: What gets measured is rarely what matters most. We need a different approach.

How often do you find project metrics that really help us reflect on and move toward who we are and who we are aspiring to become? As individuals? a project team? As community? As a species? Do you find your teams focused on metrics that are enlivening, empowering and will building? If not, perhaps it’s time for a deeper look at developing metrics that pull us toward learning, growth, and evolution across scales.

More simply put: What would look like to create metrics that are alive and that invite life?

For the better part of a year, CLEAR’s Executive Director, Josie Plaut, and Board Member, Jim Newman, have been exploring these questions with Bill Reed from Regenesis Group. We began by exploring the question, “What is the purpose of metrics or indicators? What are the products, consequences, and significance of the metrics we choose? And how do we participate in evolution, in a place?”

While we haven’t come up with THE ANSWER, we have arrived at what we believe, are some really good questions and a few principles to help further the pursuit.

Principles for place-based regenerative metrics

- Source metrics from the living place where you are working.

- Measure value adding processes at the largest manageable system that you plan to effect (manageable is a key idea here — it’s big enough to matter and to inspire, small enough to make a real difference).

- Keystone species are often a powerful place to work on for place-based regenerative metrics.

- Take stock of unintended consequences over time, evolving and adapting metrics and actions based on lived observation and structured reflection.

- Regenerative metrics are those that build the resources, capability, and will to continue evolving over time.

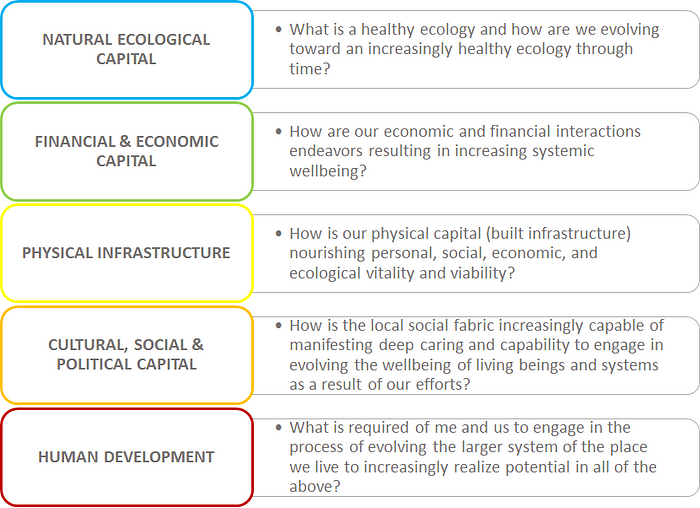

Regenerating across five capitals

Regenerative development demands that we work across capitals to add value at every scale, simultaneously. This moves us away from reductionist measures and asks us to think about what it means to work systematically. Another way to think about this is to ask the question, “What metrics will invite building capital across multiple scales?”

Through our exploration, we developed guiding questions across each of the five capitals above as a way to reconsider and identify metrics that actually matter.

A Case Story

In a recent project, it was reasonably easy to design a mixed-use development that would replicate the water quality similar to the “original” forest that once grew there, and to provide water quality far better than the chemically dependent farm that was currently on the land. By integrating green infrastructure into the design, the team was able to meet the high quality outflow requirements that the community expected for stormwater runoff using the usual metrics (e.g., Total Suspended Solids (TSS), Biochemical Oxygen Demands (BODs), reduced Nitrogen, Phosphorous, and so on).

The team discovered, however, that most people were not truly interested in the water quality alone. The concerns about the project had more to do with stopping the development from occurring, and with some justification, of course. We had to ask, “what is the real ‘impact’ we are looking for?” not simply focus on an ‘outcome’ of clean water from the development.

The answer we found was that we needed to create the conditions for life that would support the whole riparian corridor, such that the salmon and trout would return and spawn up to the headwaters. This deceptively simple metric is actually systemic in nature, requiring that all of the communities along the ravines and stream corridors needed to assess their role in cleaning the water (e.g., fertilizing lawns, salting roads, managing buffer zones, etc.).

The point of this example is to show what it means to enlarge the scope of the system — to develop a metric that has is powerful enough to inspire the entire region to join together and to understand their role in the health of the system. The metric of the salmon and trout returning to the headwaters unified and energized stakeholders toward an ongoing relationship focused on realizing an ecosystem scale health. The higher potential of this metric vs. the typical water quality metrics focused on a project boundary is self-evident.

Closing Thoughts

The example above illustrates a few key ideas on how we might begin to think about regenerative metrics:

- Regenerative metrics are sourced from place — they are not generic,

- They are big enough to matter (i.e. they demand working across capitals and across all kinds of boundaries)and small enough to manage, and

- They are simple enough to understand, yet powerful enough to engage and energize the entire community.

What’s your next step? How will you rethink metrics on your next project? We’d love to hear your thoughts in the comments section below.

Acknowledgements & Resources

The work reflected in this article was presented publicly for the first time by at the Living Future unConference during a three-hour workshop delivered by by Josie Plaut and Jim Newman with significant design contributions from Bill Reed at Regenesis Group. The foundations for the ideas represented above are based from on a long line of regenerative thinkers and practitioners.

To learn more about the foundations for this work and organizations who are working from a regenerative paradigm, check out CLEAR (Center for Living Environments and Regeneration), The Regenerative Paradigm Institute, as well as the Regenesis Institute for Regenerative Practice, who has a variety of publications and programs focused on the development of regenerative practitioners.

About the Author: Josie Plaut guides companies, municipalities, and organizational through developing capacity and action plans for regeneration and sustainability. Her work spans domestic and international projects and organizations across a variety of scales including buildings, master plans, municipal programs, coalitions, and organizational development. She is the Associate Director at the Institute for the Built Environment and Executive Director at CLEAR (Center for Living Environments and Regeneration).